The legacy of Sidney Wolff

The prolific former Director of the NOAO, Kitt Peak National Observatory, US-ELTP and the Gemini Telescope Project retires, leaving behind a legacy of telescope-facility excellence

Profile

Name:

-

Kitt Peak National Observatory

Location:

-

Arizona

Founded:

-

1958

Telescopes:

- Over two dozen telescopes

- The largest telescopes on the mountain are the 25-meter VLBA radio telescope and the 12-meter ARO Radio Telescope

- The largest optical telescopes are the 4-meter Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope and the 3.5-meter WIYN Telescope

Operational waveband:

-

Optical, infrared and radio

Altitude:

-

2096 meters

Science goals:

- To support a diverse collection of astronomical observatories

- To provide access to large astronomical telescopes to researchers across the US and around the world

- Home to the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) on the 4-meter Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope.

17 Nov. 2021

Some of us become interested in astronomy through the encouragement of a parent or teacher. Others were wowed by Apollo astronauts walking on the Moon, or images of the planets sent back to Earth by space probes. But for Sidney Wolff, it was a spelling lesson while in third grade that launched her to ultimately become a lynchpin of modern US ground-based astronomy.

Ap stars, of the type Sidney Wolff studied in the early part of her career, have surprisingly large amounts of rare elements such as chromium, dysprosium, europium, neodymium and strontium that are not ordinarily found in stars. These elements are located in patches on an Ap star’s surface, coinciding with locations of magnetic fields, and are thought to have been driven up to the surface from deeper inside the star by radiation pressure and then have moved along the magnetic field lines to concentrate in specific areas.

“I don’t remember the words, but I got fascinated by astronomy,” she told the American Institute of Physics in a 1999 interview.

Wolff studied physics and astronomy as an undergraduate at Carleton College in Minnesota in the early 1960s, before moving on to the University of California, Berkeley, for her PhD, under the tutelage of George Preston, where she studied strange ‘Ap’ stars. These are A-class stars, which have temperatures of about 10,000 degrees and are therefore a hotter and more massive kind of star than the Sun, but which are considered to behave peculiarly compared to other A-class stars because of their extra-strong magnetic fields and the presence of unusual trace elements in their atmospheres.

Ap stars were a topic that Wolff continued to research as she progressed to the new Institute for Astronomy (IfA) in Hawai’i in 1967 following a short spell as a post-doc at Lick Observatory. In particular, the IfA had funding in place to build a telescope — the first telescope — on Maunakea, the University of Hawaii 88-inch. This was completed by 1970, but to Wolff’s dissatisfaction, the telescope’s gears and computer control system were not operating as they should.

“I can’t do my research, [and] if you don’t do something about it, I’m going to leave,” she told John Jefferies, the Director of the IfA. “He put me in charge of the telescope.”

The telescope on Maunakea changed the direction of ground-based astronomy, and changed the direction of Wolff’s career. The 88-inch telescope was the first telescope to be built at an altitude greater than 10,000 feet, where the air was dry, and still, and near-infrared as well as optical astronomy could be done. Wolff managed a team who got the 88-inch telescope working as it should. The selection of Maunakea as the site for Canada-France-Hawai’i Telescope (CFHT) cemented the mountain's status as one of the top sites in the world for astronomy. The CFHT, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility and the United Kingdom Telescope all went into service on Maunakea in 1979.

Wolff worked as Assistant Director of the IfA during this time, and then Acting Director when John Jefferies departed to work for the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) as the new director of the National Optical Astronomy Observatories (NOAO) — the predecessor to NOIRLab. In 1984, she set sail for new pastures, having been offered the Directorship of the Kitt Peak National Observatory. Then, three years later when Jefferies left his post at NOAO, Wolff stepped up to become the new Director, a role that she remained in until 2001, becoming its longest-serving Director.

One of her first big challenges at the NOAO was the founding of the Gemini project, and the construction of the two Gemini telescopes on Maunakea and on Cerro Pachón in Chile.

One of her first big challenges at NOAO was the founding of the Gemini Project, and the construction of the two Gemini telescopes, one on Maunakea and the other on Cerro Pachón in Chile. These were among the first eight-meter class telescopes, and was also an international collaboration including both Canada and the UK as initial partners. This led to some conflict, as some astronomers argued it should be a US-only project, rather than having too many cooks in the kitchen, which they feared could affect its capabilities, particularly its infrared optimization.

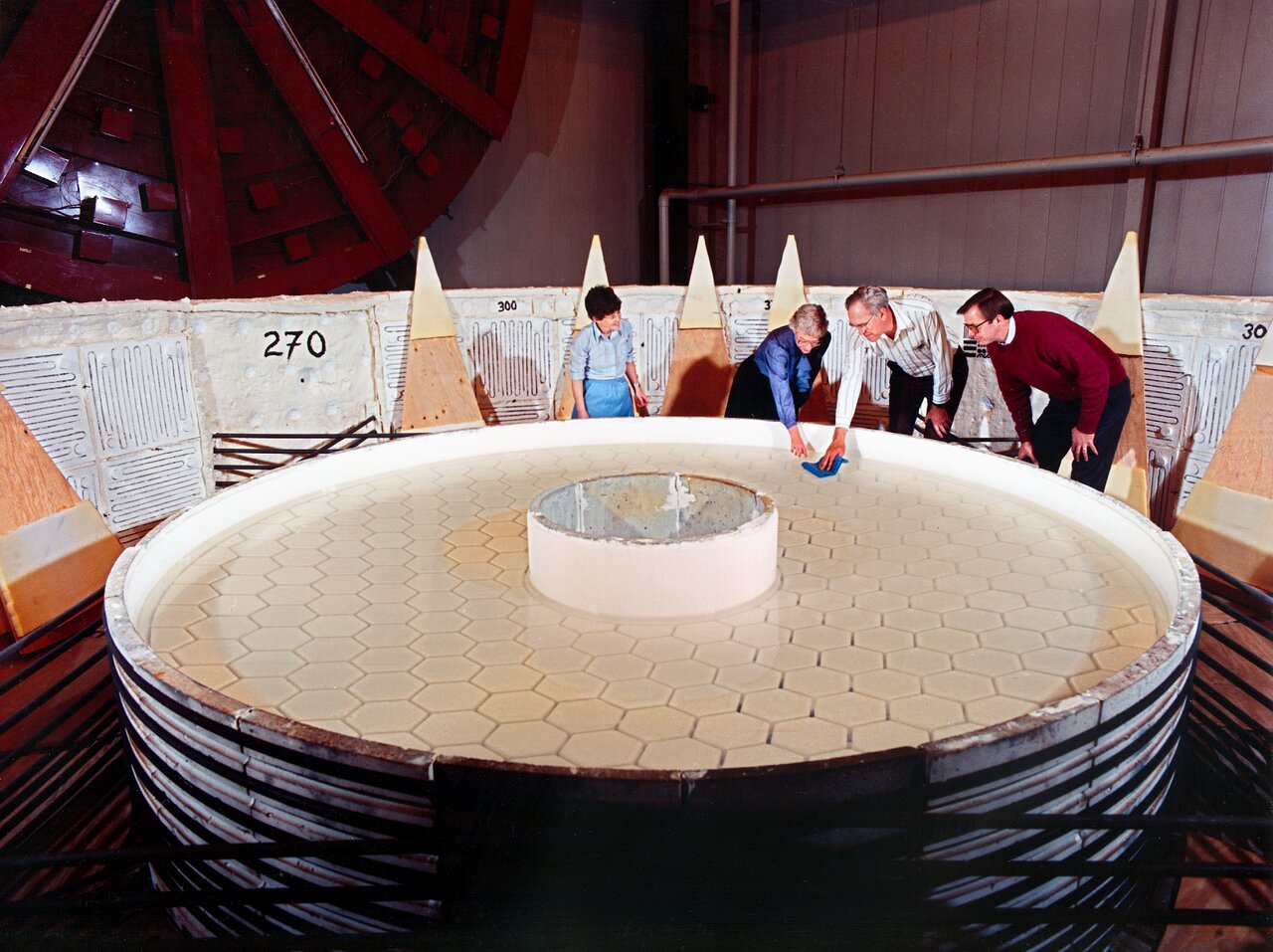

Wolff, however, was able to push through and ensure that the design of the Gemini telescopes was not compromised in any way. In particular, this meant lowering the overall mass of the telescope, because the more steel that there is in the infrastructure, the more thermal heat is stored and emitted, which damages the infrared observations and reduces dome seeing.

“For infrared optimization, image quality is crucial,” says Wolff. “We changed the design so that it was much more lightweight.”

By the late 1990s, however, Wolff and the astronomical community as a whole were looking beyond eight-to-ten meter class telescopes to even bigger observatories. The original concept in the United States was for a 30 to 50 meter telescope called the Maximum Aperture Telescope (MAXAT). Over the years this has evolved into two US-led collaborations, the Giant Magellan Telescope that will be constructed in Chile from seven 8.4-metre mirror segments to form a total aperture equivalent to a 22-meter telescope, with a resolving power of 24.5 meters, and the Thirty Meter Telescope project, which the project partners hope will be built on Maunakea. The plan is to have one giant telescope in each hemisphere. (The European Southern Observatory (ESO) is also building a 39-meter telescope in Chile.)

In recent years, Wolff has taken the lead of the US Extremely Large Telescope Project (US-ELTP), which is a collaboration involving the Giant Magellan Telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope and NOIRLab, with the intention of getting both telescope projects in a suitable position to be made the top priority in ground-based astronomy in the Astro2020 National Academy of Sciences Decadal Survey. A task that proved successful and which is the first step in a long journey that astronomers hope will lead to the completion of these giant telescopes in the next decade.

In recent years, Wolff has taken the lead of the US Extremely Large Telescope Project (US-ELTP), which is a collaboration involving the Giant Magellan Telescope, the Thirty Meter Telescope, and NOIRLab

With the two giant telescopes advancing toward construction, NOIRLab’s observatories are stronger than ever, and the stage is set for breathtaking new astronomical discoveries, Wolff is now ready to step down and retire.

It’s hard to imagine what the astronomical landscape in the US might look like if not for Wolff’s careful stewardship of so many of the country’s most important telescope facilities. Astronomers will reap the benefits of her legacy for many years to come.