John Blakeslee: A passion for telescopes

Large or small, NOIRLab’s Head of Science Staff for Observatory Support can’t get enough of the instruments that reveal the cosmos

Profile

Name:

-

John Blakeslee

Relation to NOIRLab:

-

Astronomer and Head of Science Staff for Observatory Support

Hometown:

-

Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania

Current location:

- Tucson, Arizona

Favorite quote:

-

"Never be silent whenever, wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the Universe." – Elie Wiesel, Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, 1986

20 Oct. 2021

John Blakeslee has always surrounded himself with telescopes from a young age.

So it’s little surprise to find him now working as the Head of Science Staff for Observatory Support for NOIRLab, which encompasses the research efforts of some of the largest observatory complexes in the world: Gemini, Kitt Peak and Cerro Tololo.

NOIRLab operates the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, the international Gemini Observatory, Kitt Peak National Observatory and Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

“I had a telescope as a kid, so I was always interested in astronomy,” he reminisces. Inspired by a book written by the legendary British astronomy popularizer Sir Patrick Moore, the young Blakeslee set out to learn more about the objects depicted in the crude images and drawings of that book. From those innocent beginnings, his journey took him to the University of Chicago, and his first taste of the life of a professional astronomer, under the tutelage of Donald York.

“He was the founding director of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS),” says Blakeslee. The SDSS, based at Apache Point in New Mexico, is an all-sky survey that has mapped millions of galaxies, and found countless new transient objects. Yet in 1989 SDSS was still in the planning stages.

“At the time they were building the Astrophysics Research Consortium (ARC) Telescope, which was the first telescope at Apache Point,” says Blakeslee. York hired him in 1989 as an undergrad to work at Chicago’s famous Yerkes Observatory, where they were building much of the instrumentation for the 3.5-meter ARC. Blakeslee’s job, as a ‘green’ undergrad, was to test out the telescope controls that were the prototype for the ARC. A year later, Blakeslee was hired again, but this time he spent the summer in New Mexico.

If you can build something new and useful that provides new capabilities then you’ll always have a job; you’ll always be in demand if you’re really good at that.

The ARC was a big step up from that small amateur telescope he’d had as a child, but the ARC telescope didn’t see first light until 1994. By then Blakeslee had graduated from Chicago and moved on to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to further his burgeoning career as an astrophysicist working with his PhD supervisor John Tonry. Initially, Blakeslee’s job was to process old data for Tonry, but that process turned into writing a paper and then making observations with the McGraw-Hill 1.3-meter Telescope at Michigan, Dartmouth and MIT (MDM) Observatory in Arizona.

“I got to do a lot of observing over a five-year period, and learned a lot about observatories and telescope operations,” he says. “I enjoyed the observing, and at the time it was all on your own — you were trained and then you were in charge, so you’d have the telescope for a week.”

Tonry left for the University of Hawai‘i around the time Blakeslee was completing his PhD in 1997, and would go on to build the camera for the first of the Pan-STARRS survey telescopes, as well as the ATLAS all-sky survey to hunt for potentially hazardous asteroids. Both York’s and Tonry’s expertise in building telescopes and astronomical instrumentation left a big mark on Blakeslee.

“I’d advise anyone just starting out in astronomy research that a really good field is astronomical instrumentation, because if you can build something new and useful that provides new capabilities then you’ll always have a job; you’ll always be in demand if you’re really good at that,” he says.

After a three-year postdoc at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Blakeslee enjoyed a brief spell in the UK at Durham University, before moving on to Johns Hopkins University to become a research scientist with the Hubble Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) project and then to Washington State University. In 2007 he joined the Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics in Victoria, Canada, as Senior Research Officer, but it wasn’t just the astronomy keeping him active.

Blakeslee is continuing his work on large-scale surveys, mapping and studying galaxies, and has recently authored a paper describing the strategic scientific plan for the Gemini Observatory.

“The only hobby I have is running,” he admits. “I started running races in 2009 when I moved to Victoria; there’s a big 10K race there every year, and the observatory had a team so I joined up. I ran it 7 years in a row.”

Blakeslee has to spend long months away from his family in Louisiana, a tribulation faced by many astronomers working at remote observatories. “We were apart for a long time,” he says. Compounding this was the global pandemic that left many parts of the world, including Chile, in strict lockdown, which created its own challenges. “It was pretty interesting traveling with my family during the strict lockdown in Chile when people weren’t even meant to be traveling to the country at that time.”

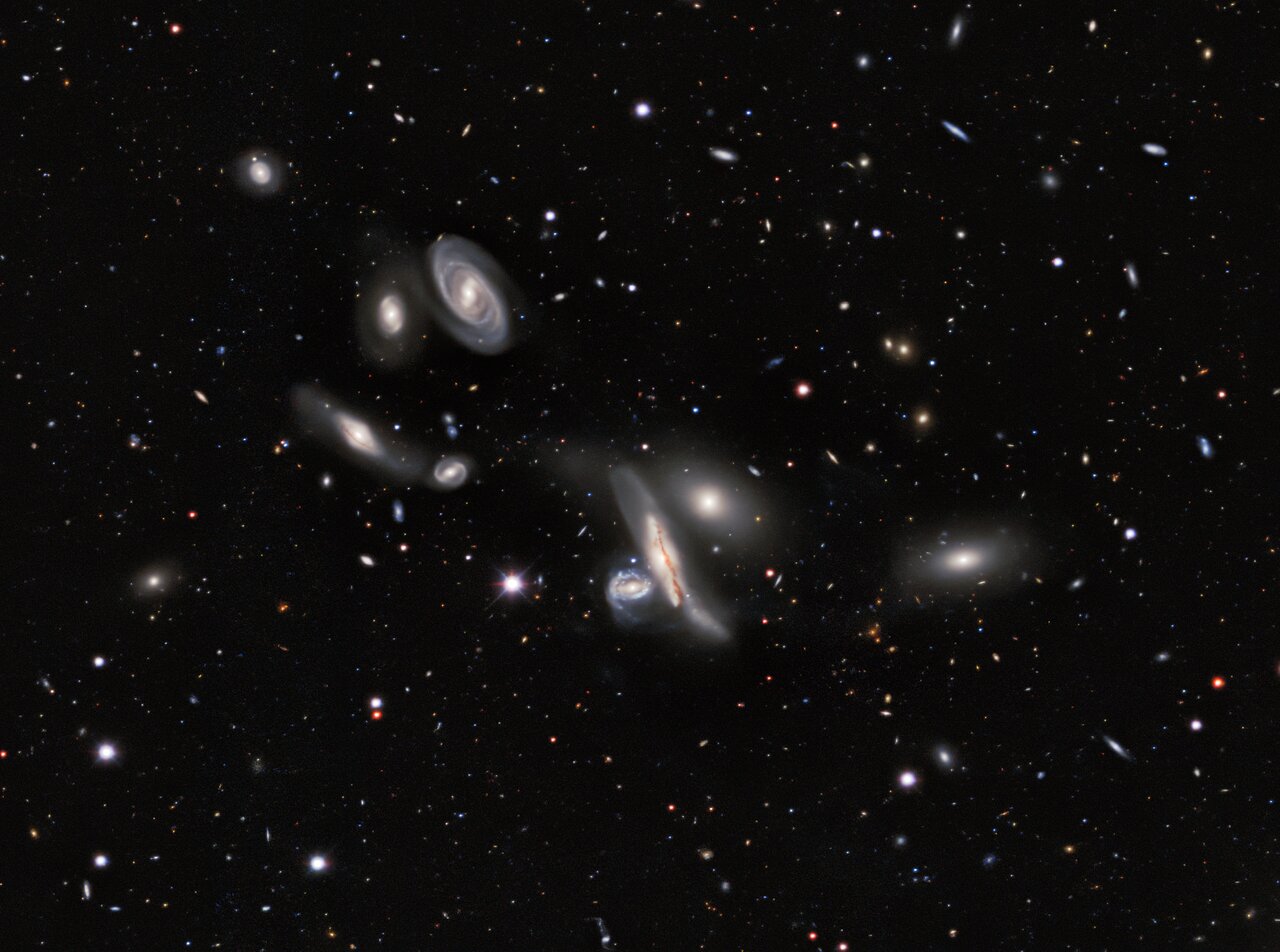

Now working for NOIRLab, Blakeslee continues his work on large-scale surveys, mapping and studying galaxies, and has recently authored a paper describing the strategic scientific plan for the Gemini Observatory. While the size of the telescopes that he uses has changed since he was a child, the joy of using them to reveal the Universe has never left him.

Links