Stéphanie Juneau: “I like to think about how science and art can interact”

The story of a NOIRLab astronomer who works and lives at opposite ends of a spectrum

Profile

Name:

-

Stéphanie Juneau

Relation to NOIRLab:

-

Associate Astronomer at NOIRLab

Shares birthday with:

-

German mathematician August Möbius

Hometown:

-

Ste-Victoire, Québec, Canada

Current location:

-

Tucson, Arizona

Likes:

-

Creative thinking, dark chocolate, coffee

Dislikes:

-

Small tasks

When I’m not at work, I’m usually…:

-

Doing art, rock climbing, hiking, or going on a sunset neighborhood walk

Favorite quote:

-

"We especially need imagination in science. Question everything.” — Maria Mitchell, astronomer

13 April 2021

Stéphanie Juneau likes to work at opposite ends of the spectrum when it comes to her interest in astronomy.

Today she is an associate astronomer at NOIRLab in Tucson, Arizona, but when she was an undergraduate in Québec, Juneau began in the pure physics program, part of which was quantum mechanics — the physics of the smallest scales.

“It was just fascinating to think about the smallest possible scales and the largest possible scales,” says Juneau. “And that’s what we can do in astronomy, from studying particles to going all the way out to the large-scale structure of the Universe.”

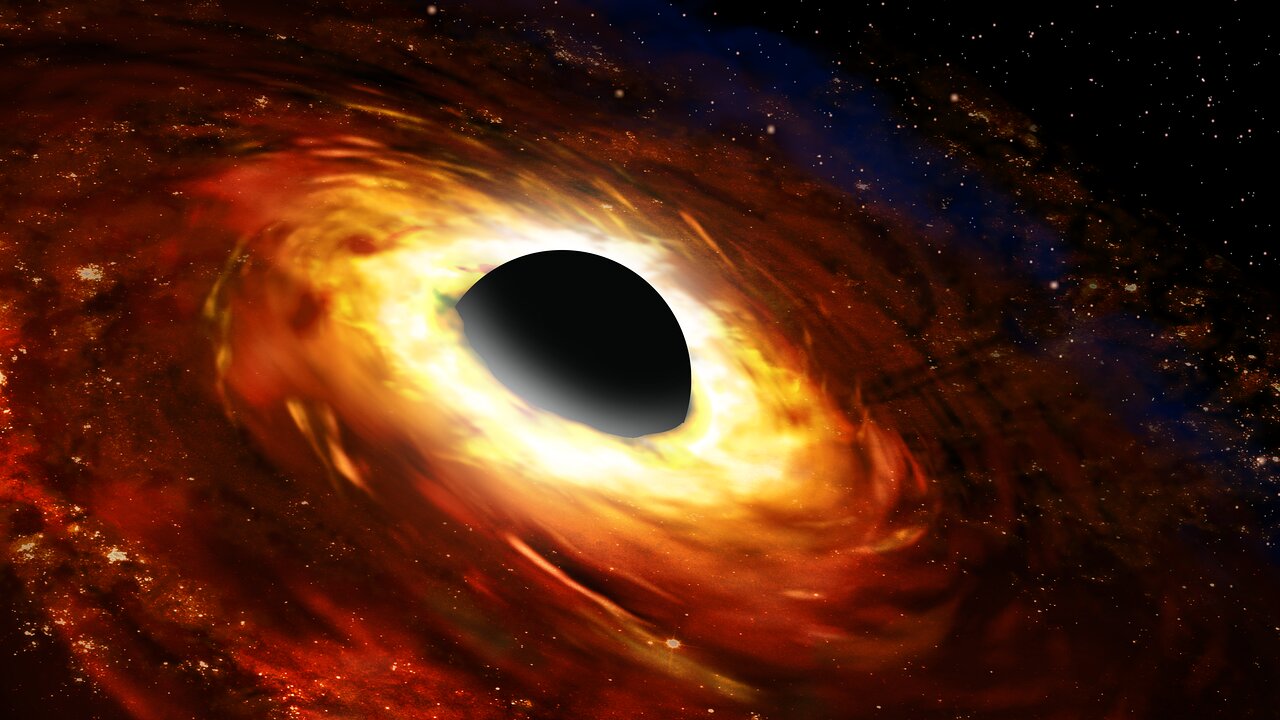

Juneau continued in astronomy, studying active black holes for her PhD at the University of Arizona, but this idea of exploring the Universe at different scales remained with her. A supermassive black hole exists at the center of almost every large galaxy, and sometimes these black holes are active, guzzling gas that is falling into them. The gas swirls around the black hole, forming an accretion disk, which grows hot and luminous and can be observed across the spectrum.

Despite what the movies tell you, black holes don’t suck up material like a vacuum cleaner. Their strong gravitational field means that they pull their surroundings — whether that’s space debris or light — towards their singularities.

“On the one hand, I’m interested in looking at a single galaxy that has an active black hole and seeing how the gas is being heated and moving around it,” she says. Yet, at the opposite end of the spectrum, her research encompasses not just single galaxies, but hundreds of thousands of galaxies at a time.

“I’m interested in population studies, and seeing what fraction of galaxies have an active black hole and how many of those black holes are growing,” she explains. The aim is to understand the growth of black holes in unison with the galaxies around them, and figure out how they affect each other.

As a member of NOIRLab’s Astro Data Lab team, Juneau also sits on the other side of the fence, developing tools for scientists to access NOIRLab’s huge datasets.

To do this requires a lot of data, and writing code to analyze that information. As a member of NOIRLab’s Astro Data Lab team, Juneau also sits on the other side of the fence, developing tools for scientists to access NOIRLab’s huge datasets. Currently, the largest dataset contains 65 billion rows. “It would take 22 days just to download it!” says Juneau. So what she and her fellow scientists in the Community Science & Data Center have done is to configure tools that allow scientists to run their own computer code to analyze the data directly on the Data Lab’s servers, without having to download it. These ‘notebooks’ — web-based interactive computational environments — make the data far more accessible to scientists and students.

Juneau’s love of working at the extremes also extends to her hobbies. Her move to Arizona wasn’t purely motivated by her career.

“My main hobby is rock climbing, and it was actually one of the reasons that I moved to Tucson for grad school, because there’s rock climbing all year around,” Juneau says, adding that the Arizona mountains are her favorite place to be whether if it's for work or play. “So the rock climbing connection is really strong with my work.”

The more difficult the climb, the better, and the same goes for the hikes across Arizona that Juneau enjoys. “I like to challenge myself. I went across the Grand Canyon, for example, from one side to the other, 24 miles, and that took 12 hours. Another time, my friends and I challenged ourselves to do the return trip too, and it took 34 hours — allowing for a few hours to sleep!”

More sedate is her interest in art. “My mom wanted me to become an artist, not a scientist!” Juneau laughs. So she combines the two, referring to it as ‘sci-art’. “I recently made a print of the Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, which was fun.” Juneau also produces art depicting female astronomers, or the constellations but with a twist — Orion as a Huntress, or the Seven Sisters of the Pleiades star cluster with their footprints gathering, standing strong instead of running away from Orion.

I like to think about how science and art can interact, and sometimes things I learn in art become applicable to my science too, so I don’t really separate them.

“I like to think about how science and art can interact, and sometimes things I learn in art become applicable to my science too, so I don’t really separate them.”

Juneau says that she sees her various projects not as a means to an end, but as something to love doing on their own merit, which is good advice for those looking to follow in her footsteps and become a professional astronomer.

“Of all the people who study for a PhD, only a fraction will end up with a faculty position,” she says. Studying for a doctorate simply as a means to win one of those coveted positions could ultimately be self-defeating. Instead, she advises prospective young students to study for a PhD for the love of doing the research.

“A PhD is hard, but if you’re doing it because you want to learn what it will teach you, and you want to discover what you’ll discover, then it isn’t a waste of time even if it ends there,” she says, likening a PhD candidate’s career to climbing a tree, echoing her own passion for rock climbing. Juneau points out that you don’t have to keep climbing the tree trunk with the hope of a faculty position: there are other branches that you could climb onto that take you into other careers. “Any branch could be a success,” she says, adding that while studying for your PhD, you will acquire a toolkit of skills, such as problem-solving and computer coding, that you can take with you into other careers. “And you’ll have your PhD,” she says.

“That’s yours to keep. Nobody can take it away, regardless of what you do next.”

Links